But it does show how women were the chosen voice for a city engaged in painful soul-searching as it attempted to rebuild itself and to negotiate its way in a rapidly changing world. It would be a mistake therefore to see this play as a radical call for female emancipation. In some ways, too, it only reinforces a traditional stereotype: men may have mucked up the city’s affairs, but the women also get it wrong. The play ends with the radical reform agenda falling to pieces as even the women balk at having to be so scrupulously fair in their sexual pursuits.Īt first sight it is a play written by a man for a mostly male audience. If a man wanted to go to bed with a good-looking woman, or a woman wanted to sleep with a handsome man, the man would first have to have sex with an ugly woman and the woman with an ugly man – to ensure that everyone got a fair share of the treats. Such equality would even apply to the sex lives of Athenian citizens. The women institute a radical reform agenda in which everyone is to be made equal in all aspects of their lives (a policy echoed in the works of the philosopher Plato, writing at this time). Their specific target is the growing disjuncture between the haves and the have-nots. Now in control, women set about reforming Athens. They infiltrate the political assembly and persuade it to hand over all power to the women.

The women of Athens are fed up with the mess men have made of the city and its affairs. In 395 BC, just nine years after Athens had suffered catastrophic defeat in war, internal political revolution and the loss of its world empire, the comic playwright Aristophanes wrote and produced a play called Women in the Assembly (Ecclesiazusae). Throughout Greece, new forms of expression for women are evident that were energetically taken up in response both directly and inadvertently to the unpredictable world around them. In Sparta, women emerge as landowners and are portrayed in training for motherhood and athletics. In Athens they appear centre stage in comic discussions of sexual and political equality and in the law courts on issues relating to citizenship. In different parts of ancient Greece women become visible for different reasons. This primarily economic drive was coupled with great political upheaval, an increasingly muddled distinction between public and private worlds and new forms of religious expression. The orator Demosthenes, writing in the middle of the fourth century, complained that they now worked as nurses, wool-workers and grape-pickers on account of the city’s penury. In response to the increased poverty that resulted, Greek women began to work outside the home. What does the tale of this brutal dawn reveal about the role of women in ancient Greece? The transformations that occurred were motivated in part by the catastrophic effects of the Peloponnesian War, the 30-year conflict which had brought democratic Athens to its knees. In a single lifetime, between the fall of Athens in 404 BC and the rise of Alexander the Great in the 330s BC, the Greek world was turned on its head.

GREEK WOMEN MANUALS

The range of female influence and experience has slowly been brought to the fore: from the divine power of the female gods to the social and religious power of female priests, from the model women of Homer to the anti-heroines of myth and drama, from women who were the power behind the throne to those who wore the crown themselves, from female-enforced prostitution to female-authored sex manuals and poems of literary genius. The result has been a change in the depth and nature of our understanding of them. Fuelled by the rapid evolution in the roles of women in modern society, historians have taken a fresh look at women in ancient Greece. Yet in the last 50 years or so a revolution has taken place. The place of women in ancient Greece is summed up most acutely by the historian Thucydides writing in the fifth century BC when he comments: ‘The greatest glory is to be least talked about among men, whether in praise or blame.’ Even ancient Athenian democracy, which the modern world honours, denied women the vote. Surviving works of art feature women in various guises, but rarely give an insight into any other kind of world except that in which women were controlled, contained and often exploited. The surviving physical evidence – temples, buildings and battle memorials – all speak of a man’s world.

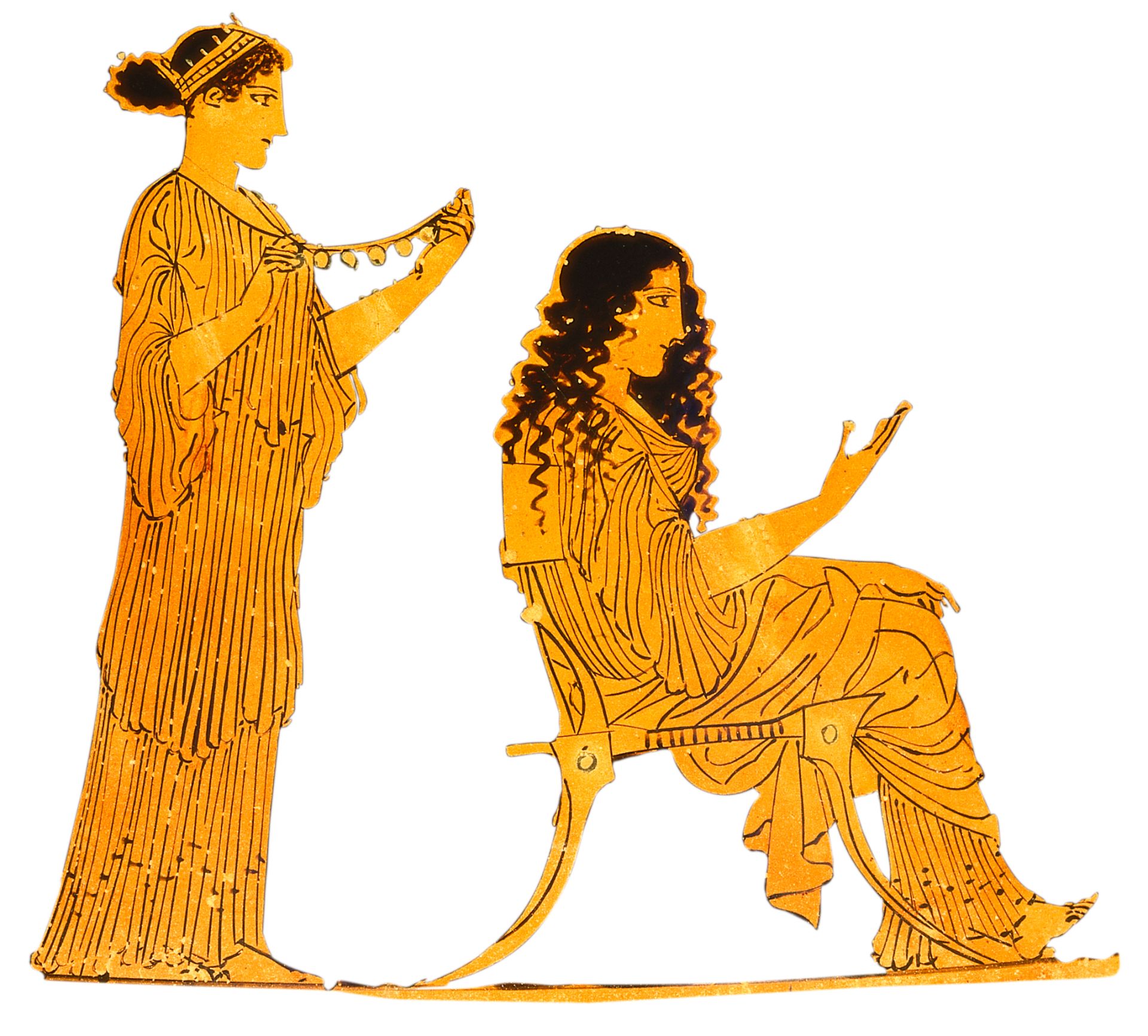

The sources that survive from ancient Greece are overwhelmingly written by men for men. Detail from a Terracotta lekythos, showing two women spinning wool into yarn and two women working at an upright loom, c.550–530 BC.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)